Happiness and Government

Governments set the institutional and policy framework in which individuals, businesses and governments themselves operate. The links between the government and happiness operate in both directions: what governments do affects happiness (discussed in Chapter 2), and in turn the happiness of citizens in most countries determines what kind of governments they support (discussed in Chapter 3). It is sometimes possible to trace these linkages in both directions. We can illustrate these possibilities making use of separate material from national surveys by the Mexican national statistical agency (INEGI), and kindly made available for our use by Gerardo Leyva, INEGI’s director of research.[1]

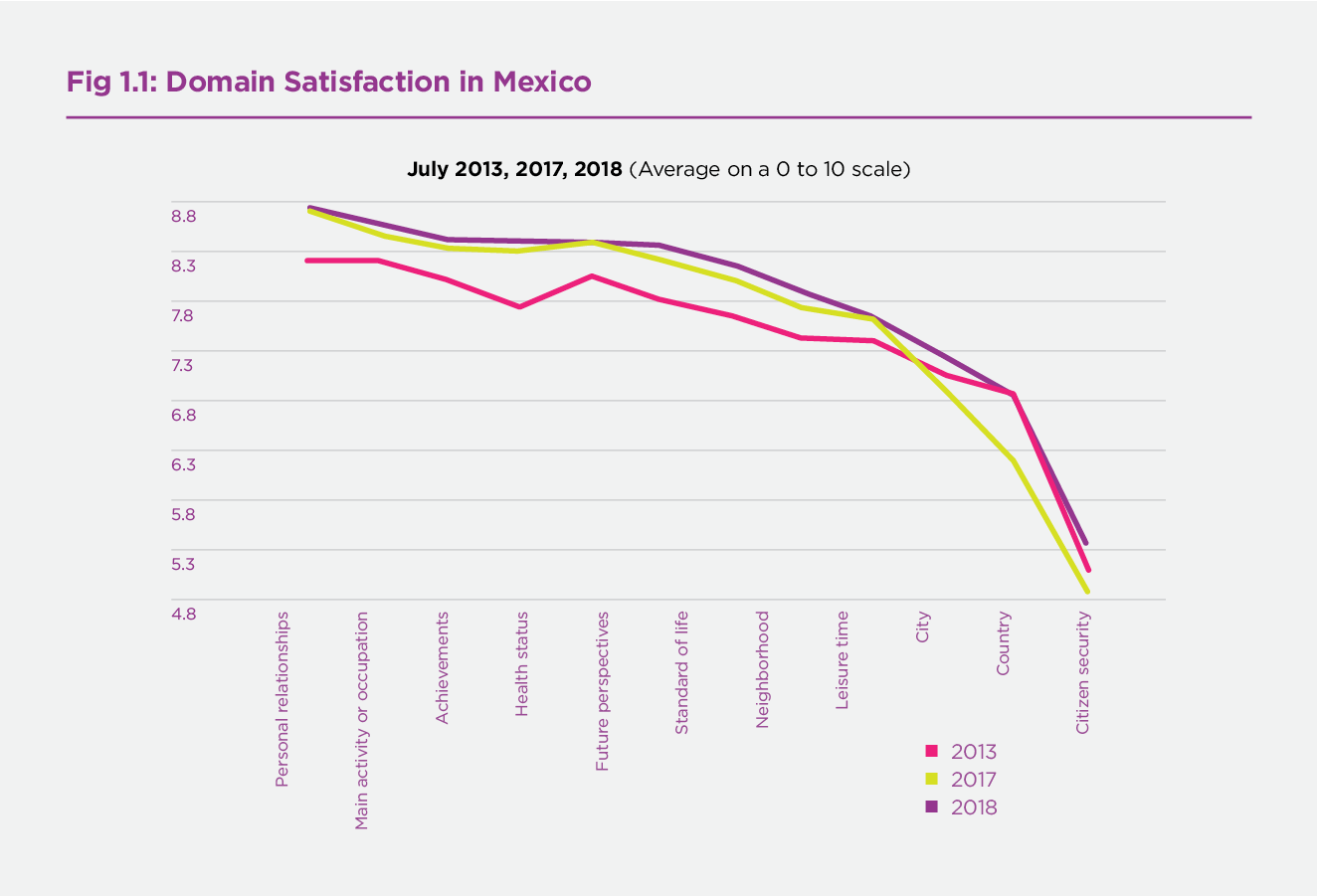

The effects of government actions on happiness are often difficult to separate from the influences of other things happening at the same time. Unravelling may sometimes be made easier by having measures of citizen satisfaction in various domains of life, with satisfaction with local and national governments treated as separate domains. For example, Figure 1.1 shows domain satisfaction levels in Mexico for twelve different domains of life measured in mid-year in 2013, 2017 and 2018. The domains are ordered by their average levels in the 2018 survey, in descending order from left to right. For Mexicans, domain satisfaction is highest for personal relationships and lowest for citizen security. The high levels of satisfaction with personal relationships echoes a more general Latin American finding in last year’s chapter on the social foundations of happiness in Latin America.

Figure 1.1 Domain Satisfaction in Mexico

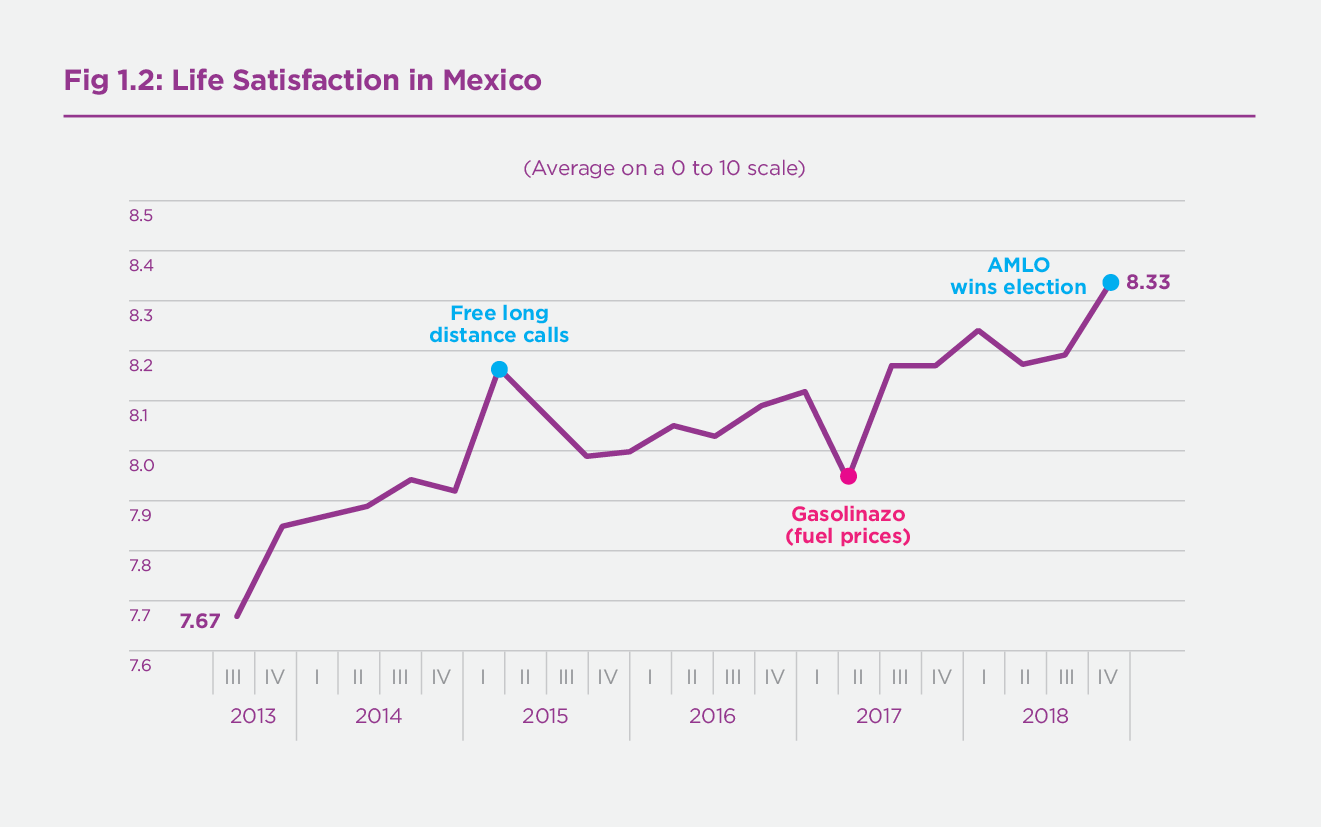

Our main focus of attention is on satisfaction with the nation as a whole, which shows significant changes from year to year. Satisfaction with the country fell by about half a point between 2013 and 2017, with a similarly sized increase from 2017 to 2018. These changes, since they are specific to satisfaction with the national government, can reflect both the causes and the immediate consequences of the 2018 national election. As shown in Chapter 3, citizen unhappiness has been found to translate into voting against the incumbent government, and this link is likely even stronger when the dissatisfaction is focused in particular on the government. Consistent with this evidence from other countries and elections, the incumbent Mexican government lost the election. Despite the achievements of the administration in traditionally relevant fields, such as economic activity and employment, mirrored by sustained satisfaction with those domains of life, the public seemed to feel angry and fed up with political leaders, who were perceived as being unable to solve growing inequalities, corruption, violence and insecurity. When the election went the way these voters wished, then this arguably led to an increase in their life satisfaction, as noted by the AMLO spike in Figure 1.2.

The Mexican data thus add richness to the linkages from domain happiness to voting behaviour by showing a post-election recovery of satisfaction with the nation to the levels of 2013. As shown by Figure 1.1, post-election satisfaction with the government shows a recovery of 0.5 points from its 2017 level, returning to its level in 2013. It nonetheless remains at a low level compared to all other domains except personal security. The evidence in Figure 1.1 thus suggests that unhappiness with government triggers people to vote against the government, and that the outcomes of elections are reflected in levels of post-election satisfaction. This is revealed by Figure 1.2, which shows the movements of overall life satisfaction, on a quarterly basis, from 2013 to 2018.

Figure 1.2 Domain Satisfaction in Mexico

Three particular changes are matched by spikes in life satisfaction, upwards from the introduction of free long distance calls in 2015 and the election in 2018, and downwards from the rise in fuel prices in 2017. Two features of the trends in life satisfaction are also worth noting. First is the temporary nature of the spikes, none of which seems to have translated into a level change of comparable magnitude. The second is that the data show a fairly sustained upward trend, indicating that lives as a whole were gradually getting better even as dissatisfaction was growing with some aspects of life being attributed to government failure. Thus the domain satisfaction measures themselves are key to understanding and predicting the electoral outcome, since life satisfaction as a whole was on an upward trend (although falling back in the first half of 2018) despite the increasing dissatisfaction with government. Satisfaction with government will be tested in Chapter 2, along with other indicators of the quality of government, as factors associated with rising or falling life satisfaction in the much larger set of countries in the Gallup World Poll. It will be shown there that domain satisfaction with government and World Bank measures of governmental quality both have roles to play in explaining changes in life evaluations within countries over the period 2005 through 2018. The Mexican data provide, with their quite specific timing and trends, evidence that the domain satisfaction measures are influencing life satisfaction and electoral outcomes, above and beyond influences flowing in the reverse direction, or from other causes.

Happiness and Community: The Importance of Pro-Sociality

Generosity is one of the six key variables used in this Report to explain differences in average life evaluations. It is clearly a marker for a sense of positive community engagement, and a central way that humans connect with each other. Chapter 4 digs into the nature and consequences of human prosociality for the actor to provide a close and critical look at the well-being consequences of generous behaviour. The chapter combines the use of survey data, to show the generality of the positive linkage between generosity and happiness, with experimental results used to demonstrate the existence and strength of likely causal forces running in both directions.

Happiness and Digital technology

In the final chapters we turn to consider three major ways in which digital technology is changing the ways in which people come to understand their communities, navigate their own life paths, and connect with each other, whether at work or play. Chapter 5 looks at the consequences of digital use, and especially social media, for the happiness of users, and especially young users, in the United States. Several types of evidence are used to link rising use of digital media with falling happiness. Chapter 6 considers more generally how big data are expanding the ways of measuring happiness while at the same time converting what were previously private data about locations, activities and emotions into records accessible to many others. These data in turn influence what shows up when individuals search for information about the communities in which they live. Finally, Chapter 7 returns to the US focus of Chapter 5, and places internet addiction in a broader range of addictions found to be especially prevalent in the United States. Taken as a group, these chapters suggest that while burgeoning information technologies have ramped up the scale and complexities of human and virtual connections, they also risk the quality of social connections in ways that are not yet fully understood, and for which remedies are not yet at hand.

Looking Ahead

We finish this overview with a preview of what is to be found in each of the following chapters:

- Chapter 2 Changing World Happiness, by John Helliwell, Haifang Huang and Shun Wang, presents the usual national rankings of life evaluations, supplemented by global data on how life evaluations, positive affect and negative affect have evolved on an annual basis since 2006. The sources of these changes are investigated, with the six key factors being supplemented by additional data on the nature and changes in the quality of governance at the global and country-by-country levels. This is followed by attempts to quantify the links between various features of national government and average national life evaluations.

- Chapter 3 Happiness and Voting Behaviour, by George Ward, considers whether a happier population is any more likely to vote, to support governing parties, or support populist authoritarian candidates. The data suggest that happier people are both more likely to vote, and to vote for incumbents when they do so. The evidence on populist voting is more mixed. Although unhappier people seem to hold more populist and authoritarian attitudes, it seems difficult to adequately explain the recent rise in populist electoral success as a function of rising unhappiness - since there is little evidence of any recent drop in happiness levels. The chapter suggests that recent gains of populist politicians may have more to do with their increased ability to successfully chime with unhappy voters, or be attributable to other societal and cultural factors that may have increased the potential gains from targeting unhappy voters.

- Chapter 4 Happiness and Prosocial Behavior: An Evaluation of the Evidence, by Lara Aknin, Ashley Whillans, Michael Norton and Elizabeth Dunn, shows that engaging in prosocial behavior generally promotes happiness, and identifies the conditions under which these benefits are most likely to emerge. Specifically, people are more likely to derive happiness from helping others when they feel free to choose whether or how to help, when they feel connected to the people they are helping; and when they can see how their help is making a difference. Examining more limited research studying the effects of generosity on both givers and receivers, the authors suggest that prosocial facilitating autonomy and social connection for both givers and receivers may offer the greatest benefits for all.

- Chapter 5 The Sad State of US Happiness and the Role of Digital Media, by Jean Twenge, documents the increasing amount of time US adolescents spend interacting with electronic devices, and presents evidence that it may have displaced time once spent on more beneficial activities, contributing to increased anxiety and declines in happiness. Results are presented showing greater digital media use to predict lower well-being later, and randomly assigned people who limit or cease social media use improve their well-being. In addition, the increases in teen depression after smartphones became common after 2011 cannot be explained by low well-being causing digital media use.

- Chapter 6 Big Data and Well-Being, by Paul Frijters and Clément Bellet, asks big questions about big data. Is it good or bad, old or new, is it useful for predicting happiness, and what regulation is needed to achieve benefits and reduce risks? They find that recent developments are likely to help track happiness, but to risk increasing complexity, loss in privacy, and increased concentration of economic power.

- Chapter 7 Addiction and Unhappiness in America, by Jeffrey Sachs, surveys a number of theories of addiction, presents evidence of rising US prevalence of several addictive behaviours, and considers a variety of possible causes and cures.

Endnotes

Figures 1.1 and 1.2 are drawn from a presentation given by Gerardo Leyva during the 2° Congreso Internacional de Psicología Positiva “La Psicología y el Bienestar”, November 9-10, 2018, hosted by the Universidad Iberoamericana, in Mexico City and in the “Foro Internacional de la Felicidad 360”, November 2-3, 2018, organized by Universidad TecMilenio in Monterrey, México. ↩︎